One of the largest coal seams in North America was discovered in central Virginia in the early eighteenth century. By 1750, bituminous coal was being mined in Chesterfield County. After being shipped down the James River by enslaved workers on ‘bateaux’ or river barges, coal was loaded onto larger vessels for export to markets elsewhere in colonial America.

In 1802, the Manchester Turnpike Company was chartered for the purpose of building a road network linking Chesterfield County with Richmond. A toll road soon opened connecting Coutts Ferry to the Falling Creek Bridge near modern-day Midlothian. Residents, however, objected to paying the toll. The road was a dirt road, and it heavy use meant that in winter, it became ‘so muddy as to be almost impassable,’ while in summer, the roads created a dust cloud ‘too thick for respiration.’

Mining operations began in the Midlothian area in the 1780s, and by the 1820s, the “Black Heath” mine was one of the largest in the region. The Chesterfield Railroad, a twelve mile-long gravity railroad was organized beginning in 1827 to connect the Midlothian mines with the shipyard at Manchester. The railroad took advantage of the natural downward slope between Midlothian and the James River by allowing gravity to pull trains loaded with coal downhill toward the docks. Opened in 1831, the Chesterfield Railroad was the first commercial railroad in Virginia and second in the United States. Other mines and rail connections soon opened.

Working in the Midlothian mines was difficult and dangerous. There were many fatal explosions deep within the shafts, which were frequently in danger of collapse. In March 1839, 53 men, mostly African American slaves, were killed when 700 feet of mine shaft collapsed and buried them. An explosion in 1844 killed 11 men and led to part of the mineshaft being closed permanently.

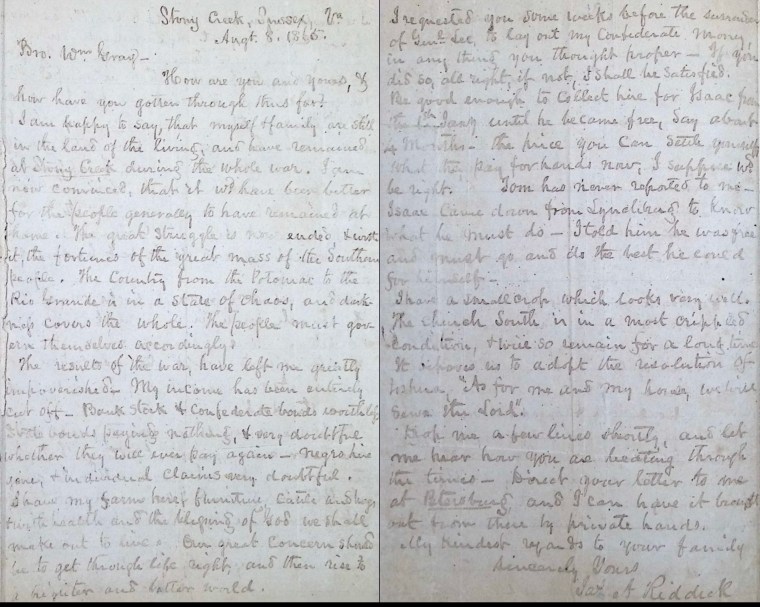

Much of the workforce at the Black Heath and other mines in Chesterfield County included enslaved African Americans hired out by their owners. Two such workers, named Isaac and Tom, were hired out to work in the mines each winter from the 1850s until the end of the Civil War. Isaac repeatedly protested to his master, Joseph A. Reddick of Suffolk, that he would rather work as a boatman on the James River. However, his requests were denied. In 1864, the two men were sent to the mines for the final time. A letter by Reddick dated August 1865 indicates that Isaac returned in the summer of 1865 “to ask what he must do.” However, Tom was never heard from again. It is presumed he may have joined a freedman’s colony.